Source: sfgate.com

Saskatchewan Canada. Hemp grain crop ready for harvest.

Its new age is a chemical renaissance. Experimental medicines extracted from hemp seed oil will treat epilepsy, migraine headaches, glaucoma, and diabetic and other nerve pain; there may even be applications for multiple sclerosis and Parkinson’s disease. The plant’s rough outer bast fibers, formerly waste, can be used in super-capacitors to store energy for electronic devices; these cooked carbon nanosheets, at least as efficient as current materials including graphene, were unveiled at the annual exposition of the American Chemical Society, held last summer in San Francisco.

More, its fibers and the cellulose-rich stem core are already producing high-impact car doors, higher-efficiency housing insulation and other building materials. And then there are cosmetics, soaps, oils, high-protein food and high omega-3 dietary supplements.

But as brilliant and economically viable as its future might be, humankind’s most ancient cultivated plant has never had an easy time in America, and there’s no reason to believe that its return is going to be accompanied by a red carpet. It’s back and it’s legal, but chances are, as in Colorado, farmers can’t legally get the seeds. You, as a citizen, can’t legally grow it. It would be easier to grow medical marijuana, hemp’s twin (same species, Cannabis sativa linnaeus).

The Drug Enforcement Agency, a policing arm of the U.S. Department of Justice, remains an anti-hemp force to be reckoned with — despite federal rules (in the Farm Bill and the Dec. 9 Congressional budget bill that cut DOJ enforcement funding) that have purportedly removed it from hemp oversight. Nineteen states have declared hemp farming to be legal, but state officials can’t guarantee there will be no federal raids. These contradictions are part of hemp’s new world: The promise of a brilliant future amid political and regulatory uncertainty.

Kentucky agriculture directors Benson Bell and Adam Watson with a DEA-contested bag of hemp seed

Legality and reality

How could a plant, whose use and cultivation dates back more than 12,000 years, be so heedlessly shelved in the first place? The answer: A bad rap as a perceived narcotic. Hemp’s role as an American pariah has roots far deeper than the Controlled Substances Act of 1970, which listed it, with marijuana, as a Schedule I narcotic in the company of heroin, crack and meth. It predates the Marihuana Tax Act of 1937, which defined hemp and marijuana as the same plant (this iron link was only broken in February last year, in the Farm Bill).

Hemp was the victim of antidrug sentiments dating back more than 150 years. Its untouchable status derives from the fallout of the Civil War, when an estimated 400,000 maimed soldiers returned home addicted to a new wonder drug, injectable morphine. Soon, opiates became the American physician’s panacea. Abuse spread, and it became America’s new bogey man. Opium dens were banned in San Francisco, smoking-grade opium was banned nationally by an act of Congress, and the Harrison Anti-Narcotics Act of 1914 restricted what was left. Soon the Temperance Movement became active, applying to liquor the same strategy of fear that had followed opium, and Prohibition was realized in 1920. Successful anti-liquor evangelicals then turned their efforts to a great new evil, “marihuana,” and ushered in hemp’s narcotic age. The anti-cannabis, often-racist propaganda (targeting Hispanics and urban blacks) that began in the 1930s is unparalleled in America for its duration, orchestration and intensity. Hemp didn’t have a chance.

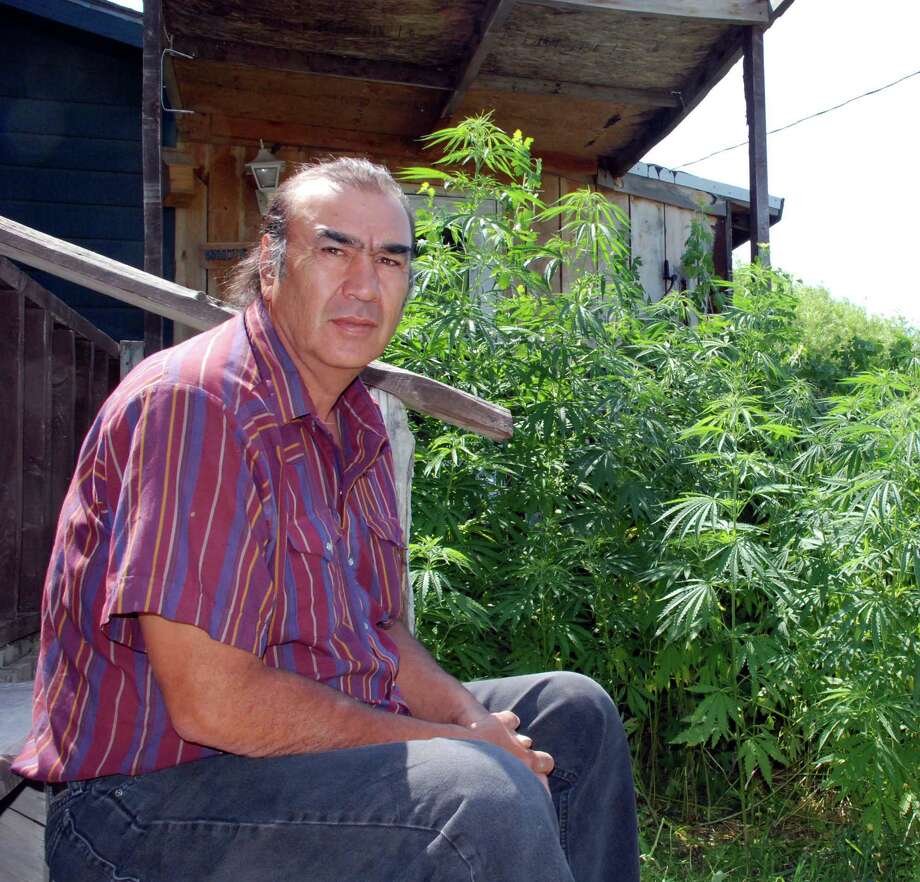

Alex White Plume sits on the back steps of his house near Manderson, S.D., on Tuesday, June 26, 2007, near some hemp plants that grew from seeds knocked off plants confiscated by federal drug agents. White Plume sought to grow hemp, a cousin of marijuana with only a trace of marijuana's drug, on his ranch on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. (AP Photo/Chet Brokaw)

Alex White Plume

In 2001 no one on Pine Ridge had to plant hemp. The DEA’s eradication technique had spread enough seed for a crop. This time, White Plume’s little brother, Percy, supervised the farming. And this time, again, the DEA swept in and cut and took the crop.

And they scattered seed in doing so. The third year, White Plume’s sister, Ramona, supervised. It grew well and 3 acres were harvested. And then the DEA seized the yield. The crop was valued by Alex White Plume at about $20,000, a very large sum in one of America’s highest poverty regions.

The White Plumes were tried in civil, not criminal, court. In 2006 the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled against them. A federal injunction bans all three siblings from ever growing any kind of cannabis again. Can the ban be lifted?

“I think I used up all those attorneys,” Alex White Plume said.

State sovereignty

But the decision against the White Plumes also signaled the dawn of sovereignty efforts by states. By 2013, nine states had approved their own version of law and declared hemp to be separate from marijuana — and legal — despite the federal Controlled Substances Act. Their rule was this: Hemp, with a THC level of 0.3 percent or less, was legal. Marijuana, with a THC level above that, would still be under the Controlled Substances Act. It was mutinous. Eleven other states passed legislation to lay the groundwork for a new hemp industry that could not yet legally exist.

As public sentiment grew, the federal government slowly took notice. On Feb. 7, 2014, hemp emerged from the shadow of its narcotic exile and became legal once again, albeit with significant restrictions. The Farm Bill, signed by President Obama, supplanted the Controlled Substances Act and separated hemp from marijuana for the first time since the Marihuana Tax Act of 1937 — though only under the auspices of state-run pilot programs. The critical 0.3 percent THC level adopted by mutinous states was now the federal threshold. But for any non-sanctioned farming, hemp remains a Schedule I drug, and growing it is still a federal offense.

By the time the landmark Farm Bill was signed, 18 states had declared hemp legal, 33 states had introduced hemp farming legislation and 22 had passed other various pro-hemp bills.

The other cannabis, marijuana, also made enormous strides: It is considered medically legal in 23 states, including California, plus the District of Columbia; Colorado, Washington, Alaska, Oregon and the District of Columbia have legalized its recreational use.

Hemp’s detractors

While hemp’s new American future is bright, its political life remains chaotic. Not everyone, it appears, is on board. Its rocky road back into American culture was apparent, and confidence in the new hemp law was so tentative that on the eve of the Farm Bill’s passage, the Colorado Agriculture Department warned potential pilot-program farmers of the uncertainties they would face. The agency said that: Although state research, according to the Farm Bill, isn’t subject to the Controlled Substance Act or the DEA, hemp seed could not be imported across state lines without violating the act; federally managed hemp crop insurance could endanger existing farm loans; and banks may be hesitant to get involved in hemp-farming loans (much as they fear handling the business accounts of growers of state-legal medical marijuana) for fear of federal raids, audits and shutdowns.

This is quite the opposite of current thinking, expressed by Hemp Industries Association Executive Director Eric Steenstra: “We see hemp becoming a standard rotation crop, for example in Kentucky.” Hemp Inc., a leading force in the nascent industry, expects a 50,000-acre North Carolina crop in 2015.

The study faded into obscurity, and the USDA hasn’t tackled the issue again. Nevertheless, it’s Steenstra’s belief that the agency is “coming around on this topic.”

“The report has been long discredited … and the USDA appears open to hemp, supportive, and there may be ways (it will become involved) in the future.” Very likely, financially.

The DEA

“The federal judge started as a sort of mediator,” said Patrick Goggin, co-counsel for Hemp Industries Association, which was involved in the case. “Finally, the DEA capitulated on the permit to farm hemp, but maintained authority over the importation of seed.” The agreement isn’t formal, but it will provide a working structure for control during hemp’s initial reintroduction.

But does the DEA have legal jurisdiction at all? The Farm Bill places pilot program policing in the hands of state departments of agriculture or state university systems, and the DEA’s parent, the Department of Justice, has had its hemp and medical marijuana policing funds restricted by Congress.

“It’s our position that the DEA has no authority,” Goggin said, “but the object was to get the seed in the ground” in time for the growing season. The bargain was struck. The seeds were released after the agreement, but Goggin noted, “I do not feel confident in the DEA.”

The following month, the DEA again seized hemp seed bound for the newly legalized pilot programs; this time it was bound for Colorado from Canada, where supervised hemp farming has been legal since 1998, after four years of pilot programs. Colorado’s law encourages hemp farming under state license, and the state issues research and development permits to individuals. No problem there, but farmers have to get seed and there’s no seed in the state. The import question has been skirted there by working under a sort of “don’t ask, don’t tell” system: If farmers can get seed, they can grow it under the program. The DEA, however, is like the fox outside the fence. As it stands, the federal agency will be working with Colorado, California (this year) and other states regarding seed acquisition.

After the seizures, the association attorney Goggin said, “We want to remove jurisdiction from the DEA; it inhibits investment for fear of prosecution.”

However, a rehash of the memo in February 2014, cautions at length about money laundering and banking — a chilling effect already noted by those involved in hemp pilot programs.

“For the Native Americans, it has always been an issue of tribal sovereignty,” he said. “They (Congress and the Department of Justice) are trying to acknowledge the treaties, and I appreciate the attorney general in this. We feel that marijuana could be used medically to address alcoholism, for example, brought on by conditions of poverty.”

Hemp has a viable future nationwide, and especially in California. The ancient plant can adapt, through selective breeding, to many environments; this is part of its history with humankind. As the Marihuana Tax of 1937 and the Controlled Substances Act of 1970 fade into history, and legal inconsistencies are overcome through new legislation if not outright disobedience, Cannabis sativa linnaeus is poised, once again, to become America’s “billion-dollar crop” — a crop in need of an industry.

In this Oct. 5, 2013 photo, a volunteer walks through a hemp field at a farm in Springfield, Colo. during the first known harvest of industrial hemp in the U.S. since the 1950s. (AP Photo/P. Solomon Banda)

(Continued next week in Insight)

Brooks Mencher is a Chronicle staff writer. E-mail: bmencher@sfchronicle.com

Hemp’s American century

1914: The Harrison Anti-Narcotics Act is passed. Mandated transporters, sellers and possessors of narcotics to pay a tax and keep records for the Internal Revenue Service of the Treasury Department. The first restriction-by-taxation act.

1916: USDA Bulletin 404 urges use of hemp paper due to the rapid cutting of U.S. forests for pulp.

June, 1930: Federal Bureau of Narcotics established within the Department of the Treasury; tasked with drug enforcement. Prohibition enforcer Harry J. Anslinger appointed director; he initiates a lifelong battle against marijuana and hemp: “To legalize marijuana would be to legalize slaughter on the highway,”

1937: Marihuana Tax Act, restricting cannabis through taxation and IRS (Treasury) mandated record-keeping, using 1914 Harrison Act strategy of restriction through taxation

1937: Anslinger’s “Marijuana, Assassin of Youth” published

1938: Canada bans hemp production

1941: Henry Ford unveils a car with parts made from hemp that runs on hemp ethanol

1942-1945: Hemp for Victory campaign, in which U.S. overlooks anti-hemp laws to produce rope for the war effort

1957: America’s last hemp producer, Rens Hemp Company of Wisconsin, shuttered: oppressive operating regulations

1967: Senate approves international treaty ratifying the Single Convention on Narcotics, forcing a ban on marijuana.

1968: Federal Bureau of Narcotics, in the Treasury Department, is absorbed by the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs, part of the Department of Justice

1970: Comprehensive Drug Abuse and Control Act of 1970 becomes law, Nixon administration. Expanded federal law (1937 Act), keeping hemp within the legal definition of marijuana, making both Schedule I narcotics

1971: President Nixon declares “war on drugs,” June 17, creates drug abuse prevention office

1973: Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs is absorbed along with five other drug-related federal agencies or departments into the DEA, Drug Enforcement Administration, under the DOJ

1996: California approves Prop. 215 legalizing, regulating medical marijuana

1998: Canada legalizes controlled hemp cultivation

1999: North Dakota becomes first state since 1937 to legalize and set regulations for cultivating hemp

2000: DEA wins case against New Hampshire Hemp Council, can still prosecute hemp producers, hemp remains Schedule I narcotic

2004: DEA loses case against Canadian hemp imports to U.S., which it seized in 1999, claiming that trace amounts of THC made hemp-food imports narcotic

2002: California Gov. Gray Davis vetoes state hemp farming bill

2006, 2007, 2008, 2011: California hemp farming act vetoed by Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger

Sept. 27, 2013: Gov. Jerry Brown signs California bill by state Sen. Mark Leno allowing farmers to grow hemp when the federal government finally gives the green light

2014: Obama signs the Farm Bill

Hemp isn’t marijuana

The only difference between the two is the level of the active psychotropic chemical delta-9 tetrahydrocannabinol, or THC. In industrial hemp, it is usually (and now, legally) 0.3 percent or less. In marijuana, it ranges between 10 and 30 percent. A second cannabinoid, cannabidiol or CBD, is also produced in both variants, and it counteracts the effects of THC. CBD has potential medical applications, especially regarding epileptic seizures. Cannabinoids, unique to cannabis plants, may number 60 or more, but THC and CBD are the major players.

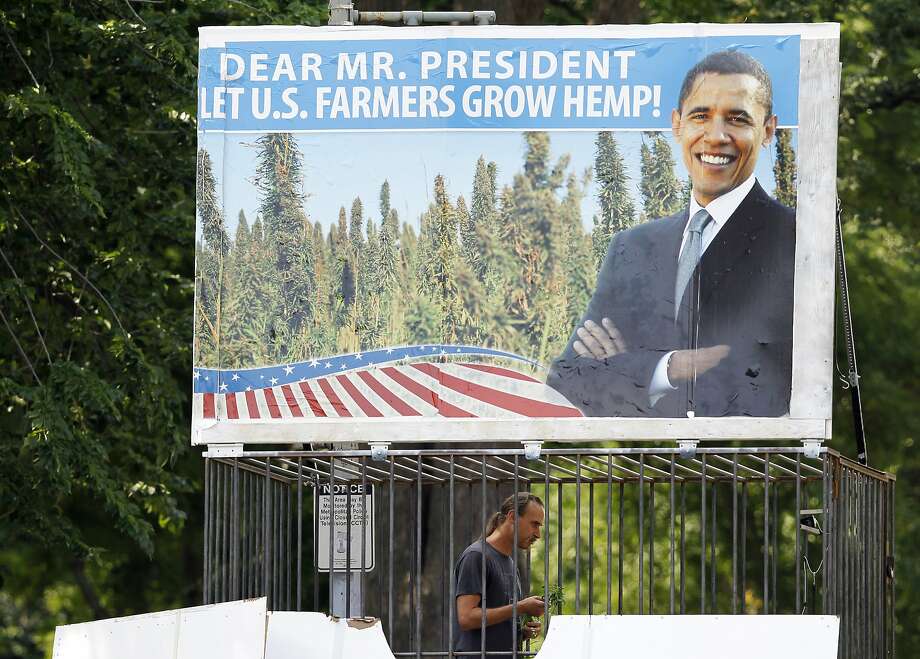

David Bronner, CEO of Dr. Bronner's Magic soaps, stands in a cage holding hemp during a hemp protest, Monday, June 11, 2012, in Washington. (AP Photo/Haraz N. Ghanbari)

No comments:

Post a Comment