By Steven Wishnia

Source:

truth-out.org

Powerful politicians across the country are pushing to bring hemp back.

The American hemp industry, revived in the 1990s in a wave of cannabis-fueled environmentalism, now sells $450 million a year of products from hemp-oil soap to hemp-coned speakers for guitar amplifiers, according to an industry trade group. Yet all the raw material used for these products, from fiber to hempseed oil, has to be imported, as it’s still illegal to grow hemp in the United States.

The Industrial Hemp Farming Act of 2013, introduced in the House on February 6 by Rep. Thomas Massie (R-KY), would end that. It would amend federal drug law to legalize growing cannabis that contains less than 0.3% THC. Its 28 cosponsors include Kentucky Republican John Yarmuth and Collin Peterson of Minnesota, the ranking Democrat on the House Agriculture Committee. Mostly Democrats, they span a geographic and ideological spectrum from Dan Benishek, a conservative Republican from Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, to Barbara Lee of Oakland, California, former chair of the Congressional Black Caucus.

“Industrial hemp is a sustainable crop and could be a great economic opportunity for Kentucky farmers,” Massie said in a statement announcing the bill. “Tobacco is no longer a viable crop for many of us in Kentucky and we understand how hard it is for a family farm to turn a profit. Industrial hemp will give small farmers another opportunity to succeed.”

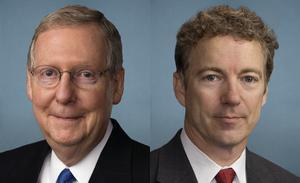

Similar legislation failed to get even a committee hearing in the 2011-12 session of Congress, but supporters are optimistic. On Feb. 14, four senators—Minority Leader Mitch McConnell and Rand Paul of Kentucky, along with Oregon Democrats Ron Wyden and Jeff Merkley—introduced a companion bill.

McConnell also recently endorsed a Kentucky state bill to allow hemp farming if the federal law was changed to permit it. State Agriculture Commissioner James Comer is pushing that measure, against opposition from police groups who claim it would make it difficult to enforce the laws against growing marijuana. The Kentucky Senate’s agriculture committee approved it unanimously on Feb. 11.

“The utilization of hemp to produce everything from clothing to paper is real, and if there is a capacity to center a new domestic industry in Kentucky that will create jobs in these difficult economic times, that sounds like a good thing to me,” McConnell said in a statement issued January 31. Hemp Industries Association spokesperson Tom Murphy says the e-mail he got with that news had the subject line “Are you sitting down?”

Hemp plants grown to produce oil or fiber are of the same species as cannabis grown for marijuana, but their genetics and the way they are cultivated are as different as a Chihuahua and a Great Dane. Cannabis plants grown for marijuana are bred for high THC and given enough space to branch out so they can produce buds. Cannabis plants grown for hemp have much lower THC and are packed densely—typically 35 to 50 per square foot—because the stalks are the most valuable part.

Cannabis’ first known use for fiber, in Taiwan about 8000 BCE, predates its first known use as an intoxicant by thousands of years. In the 18th and 19th centuries, hemp was a significant crop in the U.S., with Kentucky the main producer and the fibers used to make rope, cloth and paper. The industry declined in the late 19th century, as technological advances made cotton easier to harvest and process, and sisal and jute imports from Asia provided cheaper materials for rope.

By 1937, when the federal Marihuana Tax Act levied a punitive $100-an-ounce tax on marijuana, hemp was not an important enough crop to be included in the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s annual “Farm Outlook” forecast. The 1937 law did not actually outlaw the cannabis plant, and it exempted hemp stalks and products such as fiber or oil, but it required growers to pay $1 to get a permit from the federal government—not an insignificant sum in the Depression, when millions of farmers made less than $12 a week. (No sustainable evidence supports the widespread belief that marijuana prohibition was pushed through by a Hearst-DuPont-governmental conspiracy to eliminate hemp as competition for wood-pulp paper, nylon, and polyester.)

Hemp farming revived briefly during World War II, after the Japanese occupation of the Philippines cut off the supply of sisal, but by the late 1950s, it was gone. The Controlled Substances Act of 1970 defined growing any cannabis plant as cultivation of marijuana, a felony.

As federal drug law bases penalties on quantity, on the number of plants grown, the densely packed cultivation of hemp plants would thus bring harsher punishment than a marijuana plot of the same size. Growing hemp on a plot 100 by 10 feet—less than 1/40 of an acre—“is enough to get 20 to life,” says Murphy. Even if the federal government did not want to prosecute hemp farmers, he adds, it could seize their property and equipment as tools of crime. Under forfeiture law, the farmer would have to prove his or her innocence in court to get anything back.

From 2000 to 2002, an Oglala Sioux farm family tried to grow hemp on the Pine Ridge reservation in South Dakota, but Drug Enforcement Administration agents destroyed their crop each year. In 2006, the federal Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals held that the Controlled Substances Act prohibited growing any kind of cannabis, and that federal law superseded the permission they’d received from the Oglala tribal government.

As with medical marijuana, state governments have been friendlier to hemp. Eight states (Colorado, Maine, Montana, North Dakota, Oregon, Vermont, Washington, and West Virginia) have enacted laws legalizing farming, using the 0.3 percent THC standard to distinguish it from marijuana. Colorado’s Amendment 64, the marijuana-legalization initiative passed by voters there last November, directs the state legislature to enact regulations for hemp farming by July 2014. Eleven more states have approved other pro-hemp measures, such as authorizing studies or passing resolutions urging the federal government to legalize it. California’s legislature voted to create a pilot hemp-farming project in several counties in 2011, but Gov. Jerry Brown vetoed the bill, citing the federal ban.

North Dakota granted a hemp-farming license to state Rep. David Monson in 2007, but he was never legally able to grow any. He filed two lawsuits against the DEA challenging the prohibition, but in 2010, the Eighth Circuit turned him down, upholding a lower-court ruling that as hemp was cannabis sativa, it was legally the same as marijuana.

Canada, however, distinguishes between the two varieties of the plant. It legalized hemp cultivation in 1998. Farmers must be licensed and obtain approved low-THC seeds. Plants can be tested to ensure they contain less than 0.3 percent THC. Hemp is also legal in about 30 other countries, with China and France (where it was never outlawed) the leading producers. Eastern European countries like Romania and Hungary are trying to revive and modernize their hemp industries.

“You could outlaw heroin, but you don’t have to outlaw poppy seeds on your bagel or muffin,” says Eric Steenstra, head of the VoteHemp lobbying group. “It’s not like anybody’s going out to the Canadian hemp fields and stealing it and smoking it.”

The Kentucky bill would require hemp farms to have at least 10 acres.

Inside the Hemp Industry

Despite the federal ban on growing hemp, the industry has grown. In 2011, the Hemp Industries Association estimated U.S. hemp-product sales at $450 million, with about $130 million from food and body-care products such as Dr. Bronner’s hemp-oil soap and the Body Shop’s hemp hand lotion, and the rest from clothing, auto parts, building materials, and more. As no hemp is legally grown in the U.S., it has to be imported—and imports of hemp raw materials reached $11.5 million in 2011, more than quadruple what they were in 2000, according to federal trade statistics.

“Even after the Great Recession, the hemp industry continues to grow,” says the HIA’s Tom Murphy. Canada provides most of the seeds and oil used in food and body-care products, China most of the fiber used in textiles, and Europe a mixture of seeds, hurds, and fiber, he adds.

The industry hasn’t grown in the direction expected when it began. The original ’90s “hempsters” were mostly pot-legalization activists inspired by the hemp-can-save-the-world vision of the late Jack Herer’s The Emperor Wears No Clothes. If we used hemp for paper and clothing, they believed, we wouldn’t have to clearcut forests for pulp or spray cotton fields with weed-killers and insecticide.

The problem, says Steenstra, was that many hempsters were motivated by “great love for the plant,” but “didn’t have any background in retail.” Imported hemp was expensive. There were practical obstacles to manufacturing and marketing hemp paper and fabrics. The result was a major shakeout of businesses in the late ’90s. Hemp Times magazine, a High Times spinoff covering the hemp trade, folded in 1999. Steenstra and his business partner, Steve DeAngelo, sold their hemp-clothing company, Ecolution. (DeAngelo now runs the massive Harborside medical-marijuana dispensary in Oakland, Calif.)

Instead, the main growth has been in food and body-care products, auto and airplane parts, and construction materials. The DEA attempted to ban food products made from hempseed meal or oil, but in 2004, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals overruled it, saying hemp food contained a negligible amount of intoxicant. Since then, hemp food and body-care product sales have grown steadily, says Steenstra, rising by more than 16 percent from 2011 to 2012.

One new product is car-door liners. Manufacturers such as Flexform Technologies in Elkhart, Indiana, and Johnson Controls’ German plant take felt-like mats of non-woven hemp fibers, spray them with resin, and then press them into the appropriate shape. BMW and Ford use the light, strong material in their cars’ doors, and similar products are used in airplanes, says Steenstra.

“Hempcrete,” a lightweight concrete-like insulating material that can be poured into molds or used in blocks, is made by mixing the hurds, the woody core left after the fiber is stripped off the stalk, with lime and water. An English brewer and wine society have built warehouses with it. At Clay Fields, a green affordable-housing project in the English town of Elmswell that opened in 2008, the 26 houses are built from hempcrete surrounding a weight-bearing wood frame, protected on the outside by about an inch of lime-render cement.

Lime Technology, a British green-construction-products firm that supplied the hempcrete for Clay Fields, touts it as a much better insulator than conventional building materials, reducing the need for heating in winter and air-conditioning in the summer. It requires much less energy to produce than regular cement, it absorbs carbon dioxide from the atmosphere as it dries, and “site cleanup is easy. Simply till it into the soil.”

Going Legal

One problem for the industry is that hemp’s decades of illegality have left almost no infrastructure for growing, processing and selling it. As no hemp has been grown legally in the U.S. since 1957, says Murphy, many parts of the industry would have to be re-established virtually from scratch. To begin with, all the seed stock is gone, except for feral ditchweed.

“You’d have to breed again for varieties that work well here,” he says. Kentucky was once a major hemp producer, and it also provided seeds for strains better suited to different latitudes, such as Wisconsin. There were also strains bred for fiber or for larger seeds that yielded more oil. Currently, Murphy says, Canada uses mostly Russian and European stock. Those seeds could also be cross-bred with local feral strains.

This lack of infrastructure has been a major barrier to producing hemp clothing and paper. Building a new decorticator mill for hemp paper would cost more than $100 million, says Murphy.

Several small companies are using hemp for specialized products such as archival-quality, filter, or cigarette papers, but its most likely general use will be when mixed with recycled paper, says Steenstra. “Blend in 10 to 15 percent hemp, and it’s great for making better-quality recycled paper,” he says. When paper gets recycled, he explains, its fibers get shorter, and the long fibers of hemp strengthen it.

There are similar issues with clothing. Though Calvin Klein, Ralph Lauren, Giorgio Armani, and several lesser-known manufacturers are using hemp in clothes, “the whole textile industry is built on short-fiber cotton and synthetics,” says Steenstra. “There’s no infrastructure for processing hemp fiber into textiles.”

Hemp oil for biofuel, another use dreamed of in the ‘90s, is unlikely to be practical. At 50 gallons per acre, even if every acre of U.S. cropland were used for hemp, it would supply current U.S. demand for oil for less than three weeks.

On the other hand, the hemp-food industry is “pretty well settled,” says Murphy. If hemp growing were legalized in the U.S., he adds, a lot of Canadian processors would probably open facilities here. Legalization would also help hemp food break out of its niche-market status. If it received “GRAS” (Generally Recognized As Safe) status from the Food and Drug Administration, major brands would be less reluctant to use it. Until then, he says, Coca-Cola won’t put hemp milk in Odwalla Future Shakes, and we’re not likely to see hempseed Clif Bars.

Canada’s experience illustrates the problems of developing a new industry, says Murphy. Hemp farming there has been through two boom-and-bust cycles since it was legalized in 1998. The nation’s production leaped to 35,000 acres in 1999 and plummeted to about 4,000 in 2001, according to a report by the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development in Alberta, Canada’s main hemp-producing province. It soared to 48,000 acres in 2006 and fell to less than 10,000 two years later.

Business factors explain those fluctuations, says Murphy. When hemp was legalized, more than 200 Canadian farmers signed contracts to grow it for an American outfit called Consolidated Growers and Processors. It went bankrupt in 2000 and stiffed them for more than $1 million.

Farmers got back into it after the hemp-food industry burgeoned, aided by the end of the U.S. ban and a German inventor modifying a buckwheat-shelling machine to process hempseed. But there were not enough buyers or processing facilities to handle the bumper crop of 2006. “They were growing on spec,” says Murphy. “You really have to have a good contract.”

Since then, production has been rising again. It reached almost 39,000 acres in 2011, according to the Alberta report. The Canadian Hemp Trade Alliance projects that the area planted will reach 100,000 acres by 2014.

In 2009, the most recent figures available from the European Industrial Hemp Association, about 45,000 acres (18,000 hectares) of hemp were planted in the European Union. More than half was in France, with the U.K. and Poland following.

In contrast, the U.S. Department of Agriculture estimates that 9,461,000 acres of cotton were harvested in the U.S. in 2011—a year in which more than one-third of the nation’s crop was wiped out by severe drought, with farmers in Texas and Oklahoma forced to abandon more than 5 million acres, more than half of what they planted. The amount of cotton harvested in the mostly desert state of New Mexico, 61,000 acres, was more than all the hemp planted in Canada.

Still, it wouldn’t take that much land for hemp to have a significant impact. In 1943, when the U.S. hemp industry was revived to make rope, twine and parachute webbing for the war effort, about 146,000 acres were harvested, with a yield of about 70,000 tons.

“It would be nice to have the hemp grown here,” says Murphy.