Source: agupdate.com

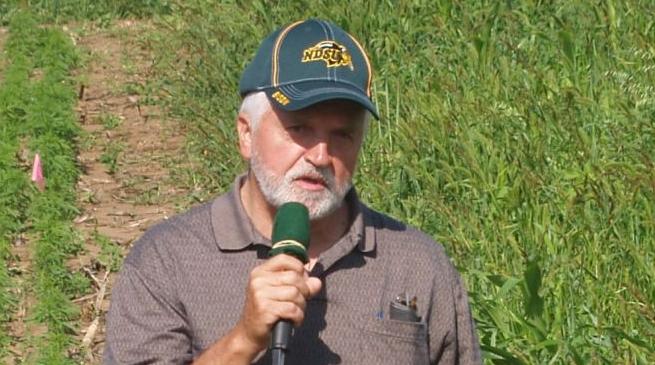

Burton Johnson, NDSU Agronomist and professor, talks about industrial hemp in the hemp plots at DREC during field days.

Like tiny Christmas trees, industrial hemp plants were growing in a strip at the NDSU Dickinson Research Extension Center on July 13, where plants ranged in height from 3-inchers popping out of the soil to some nearly a foot tall.

Producers from western North Dakota/eastern Montana ‘circled the wagons’ to hear NDSU’s longtime researcher on industrial hemp, Burton Johnson, agronomist and professor in the plant sciences department, speak at field days.

“I waited 20 years to do research on this crop right here – industrial hemp,” Johnson said, explaining he first wanted to research hemp in 1988 when some of his current NDSU students were not yet born.

While there are only a couple of producers growing hemp in the region, the interest remains high.

“When we hear about these new crops, we have seen them come and go. But sometimes these new crops stay. Canola stayed. Peas, faba beans have stayed. This crop is newish too,” he said, “but we know there is a lot more than research that must occur before you decide to grow it.”

Johnson talked about some of those reasons and what might occur with industrial hemp in the Farm Bill, as well as some agronomic decisions that producers should look at as they make their decisions about hemp in the future.

First of all, growing hemp is a lot like growing other crops, he explained.

Best management practices still apply. Those practices include selecting the variety, including yield and type; the seed, including quality and treatment; the seedbed, including crusting and saturated soils, and creating stand establishment, including date, depth and rate.

Understanding the industrial hemp plant

“Hemp varieties can be a mixture of male and female plants, or varieties can have both sexes on the same plant, only in different parts of the plant, like corn,” he said.

There are varieties for grain, some for fiber and some are dual purpose.

Seeding depth ranges from a half-inch to 1 inch, and the narrower the row spacing, the better.

“A popular row spacing for producers is 6 to 7 inches up to a foot between rows,” Johnson said. “The narrower the row spacing, the faster we get to leaf canopy closure.”

Seed germination ranges from about 80 percent to the low 90s, but mortality is generally higher than for corn, soybean or wheat. Mortality ranges from 25 to more than 50 percent, depending on conditions at and after planting.

Fertilizing the crop is “often stated as being similar to what a good wheat or canola crop would require on your farm.”

The emergence stage, active hypocotyl, like canola and sunflower, is when the industrial hemp plants come out of the ground.

This is followed by a vegetative growth period and then reproductive growth.

“Some of the plants at DREC are in the cotyledon stage because of late emergence, while others have four pairs of leaves on the main stem,” Johnson said.

When the leaves change from opposite to alternate on the main stem, flowers will soon begin to appear on the male plants.

“The number of male and female plants is about 50:50 with perhaps a few more female plants.

“The male hemp plants are generally taller because they reach the flowering stage first,” Johnson said, pointing to the strip of hemp plants.

The male plants shed pollen on the receptive female hemp flowers, which are then fertilized and develop seeds.

The seeds can be cold-pressed into oil or the seeds can be dehulled and eaten raw or added to baked foods.

How do you estimate stand counts?

Johnson and Ryan Buetow, DREC area Extension cropping systems specialist, investigated the DREC industrial hemp strip before field days began.

“What do you think about this stand? If this were your field of hemp, would you be getting a bumper crop?” Johnson asked.

Producers can find out how good or bad their stand is the same way they do it for other crops. They can lay down a measuring stick and find out the distance between the rows. Then count the number of plants for a given row length and calculate how many plants there are per square foot or per acre.

“We double the population if we are growing hemp for fiber,” he said. Hempcrete is a green building material manufactured from hemp fiber.

Like any other crop, producers want to push for good yields.

“We need to get good yield and to do that, we need to have 10-12 plants uniformly spaced per square foot, about the same as for canola maybe a couple less,” Johnson said.

Canopy should be full for hemp crop

Industrial hemp has no herbicides labeled for it in the U.S. because its cousin is marijuana.

While the plants should be 10 to 12 plants per square foot, they were less than that at the DREC plot.

“Canopy cover is very important because we have no herbicides for weed control,” he said.

Where does the crop fit?

Industrial hemp is a broadleaf, like canola, field peas and soybeans.

In North Dakota, the Langdon Research Extension Center test plots have yielded from 900-2,000 pounds per acre.

“It is moist there and hemp grows well in moister soils, but it doesn’t like excessively wet soil conditions,” Johnson said.

Hemp has a good taproot that can go deep for nutrients and water, which may have saved some yield last year in the drought.

“It is not as deep of a taproot as sunflowers; it can’t go 6 feet, but it can go down 4 feet and recycle nutrients,” he said.

Researchers aren’t exactly sure how much water the plant needs.

“We haven’t grown this crop since 1940, so we aren’t sure how much water it needs,” he said.

Harvest happens around the same time as canola is harvested, which means it is usually ready to straight harvest for grain in late August/early September.

The crop would be taken off at around 15-18 percent grain moisture and dried immediately to 9 percent moisture to prevent spoilage in storage.

What the Farm Bill might do for hemp

In 1970, the U.S. regulated hemp as a Schedule 1 narcotic because of its relation to marijuana, although the THC level is negligible.

“But in 2015, a small miracle happened and is perhaps about to happen again in the 2018 Farm Bill,” Johnson said.

Universities and states were able to do research with industrial hemp under the 2014 (passed in 2015) Farm Bill.

While hemp is still linked as a Schedule 1 drug, the Farm Bill may change that if Congress makes it happen.

“Hopefully that will happen, and what it will mean is industrial hemp will be decoupled from marijuana, and that will be a good thing,” he said. “Then we can more easily market our grain, which for some producers is still sitting in the bins from last year, because of difficulties moving the grain out of state.”

Johnson pointed out there is only one major marketer in North Dakota, Roger Gussiaas, owner of Healthy Oilseeds, LLC. North Dakota would need more markets if a lot of farmers were to grow industrial hemp.

In the first year of growing industrial hemp, farmers in North Dakota grew it and it was sold for roughly 90 cents to $1 a pound.

Last summer, after the “Cinderella” year, the price per pound dropped to around 55 cents per pound.

“However, organic industrial hemp is worth about 90 cents a pound. That’s a good return,” he said.

Johnson reminded producers to compare the price to other crops like wheat and see how it fits into their farm economics.

Fortunately for North Dakota producers, research at Langdon Research Extension Center has been continuing since 2015.

At the center, varieties planted have been and continue to be evaluated for grain and fiber production, as well as for various agronomic traits such as seed mortality, seedling vigor, plant height and test weight.

Industrial hemp performance reports can be viewed at the Langdon REC website https://www.ag.ndsu.edu/langdonrec/ under Crop Production Management.

Johnson has been appointed to the Industrial Hemp Advisory Board at the North Dakota Department of Agriculture to assist with evaluating producer applications for growing industrial hemp.

No comments:

Post a Comment