Source: roanoke.com

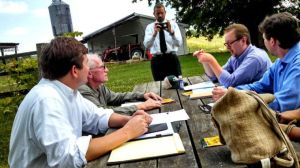

Chase Milner (from left), Virginia Industrial Hemp Coalition; former Montgomery County Supervisor Jim Politis; Richard Patterson Jr., Virginia Industrial Hemp Coalition; Del. Joseph Yost; and Jason Amatucci, Virginia Industrial Hemp Coalition, met last week to talk about upcoming hemp legislation in the Virginia General Assembly.

RINER — There was hemp fabric for clothing and backpacks, hemp seeds for snacking and a block of hempcrete for building.

There was a hemp-and-berries-and-bananas pie, and hemp paper and hemp plastic.

And there was hemp legislation, which after all was the focus of Tuesday’s gathering at Jim Politis’ farm in Riner.

Politis, the former chairman of the Montgomery County Board of Supervisors and a long-time advocate of legalizing hemp, had called together hemp activists to sit down with state Del. Joseph Yost, R-Pearisburg, to go over a proposal to allow growing the plant in Virginia. Yost hopes to file the proposal July 23, the first day that bills can be submitted for next year’s General Assembly session.

Growing hemp was banned across the United States decades ago because the plant is a variety of marijuana. With restrictions on marijuana loosening in many parts of the country, hemp advocates still emphasize the difference between the strains of cannabis grown for smoking and those grown for fiber and oil.

“Let’s just put this out there — it’s not marijuana,” Yost said.

The hemp varieties of the plant have been bred to have more fiber. More importantly to the legal distinctions, hemp plants have lower concentrations of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol, or THC, the chemical that causes the high associated with marijuana.

Yost’s proposal follows the lead of the U.S. Farm Bill that Congress passed in February, defining hemp as a cannabis sativa plant with less than 0.3 percent THC content by weight. In comparison, marijuana seized by police in 2012 had an average THC content of about 15 percent, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

The federal Farm Bill allows hemp growing for research purposes in states that pass laws to allow it. Yost said his legislation would allow commercial growing as well, anticipating what he and other advocates predict will be further changes in federal rules.

If Yost’s legislation is approved by the General Assembly, it could restore a long tradition of hemp-growing in Virgina. In 1619, just a dozen years after the founding of Jamestown, a law required settlers to grow hemp because the new colony needed rope and fabric. Later, Thomas Jefferson invented equipment to aid in processing hemp fiber. The first two drafts of the Declaration of Independence were written on hemp paper, Yost noted.

With cameras surrounding them, Yost and Politis sat down at a picnic table with members of the Virginia Industrial Hemp Coalition, and Cindy Sheaffer, the owner of the Hemp Dog Cafe in Richmond. Printouts of the draft legislation prepared by General Assembly staff at Yost’s request were spread out.

But the legislative talk lasted only minutes.

A television crew was seeking interviews. And Yost and the coalition members had already read through the text, adapted from authorizations approved in Kentucky and other states.

After Yost remarked that the House agriculture committee, where the proposal would certainly go, has a staffer who finalizes the language of such legislation, the writing part of the Riner event ended quickly.

Next was a touting of the many uses and beneficial properties of hemp. Among the listeners was Dan Brann, an area farmer who said he came to hear more about a potential money crop.

“I’ve always said I’ll grow anything that’s legal — and profitable,” said Brann, who is well known in the New River Valley for the pumpkin crop that he and a partner raise each autumn.

He had questions about what sort of equipment — rakes, balers, and more — would be needed to turn a field of hemp into a marketable product.

“If you can hay, you can grow fiber,” Politis assured him.

The U.S. market for hemp products is greater than $500 million, said the hemp coalition’s Jason Amatucci. Yet, the United States is the only industrialized nation that does not allow hemp to be grown, Yost said. The hemp products sold in the United States are made from hemp grown outside the country.

“There’s not really a major grocer you can go into and not find something made out of hemp. … There’s more out there than you realize,” Yost said.

Yost and Politis pointed to the possible jobs at processing plants that would likely follow widespread domestic growing, and to the market for biofuel made from hemp. Politis displayed a block of hempcrete made by mixing cement with hemp “hurd,” the leftover stalks and shavings after fiber is extracted, and said it had much better insulating properties than regular concrete.

Chase Milner of the coalition noted the gain in omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids in the meat of animals who have eaten feed made from hemp. Another coalition organizer, Richard Patterson Jr., described possible medical uses.

And Sheaffer talked up the Hemp Dog, made with hemp seeds and oil and served on a bun made from hemp flour. “Basically the healthiest hot dog on the planet,” Sheaffer said.

Hemp growing has been supported at the federal level by Yost’s mentor, U.S. Rep. Morgan Griffith, R-Salem.

Patterson admitted that it felt a little strange for the activists to be working with Republicans when for years, the little support that existed for hemp legalization more often came from Democrats.

“Yeah, it’s weird,” Patterson said. “But the hemp, it’s a go.”

Yost, Politis, Sheaffer and the coalition members agreed that nationally, the momentum for restoring hemp cultivation is greater than at any time since the World War II, when hemp growing was reinstated for a few years to fill military needs.

“We’re on the right side of history,” Amatucci said.

No comments:

Post a Comment