Source: theatlantic.com

Jane Harrod, a farmer in Kentucky, talks about transitioning to a different crop after the U.S. soured on cigarettes.

Since the 1960s, the number of Americans who smoke has decreased significantly; in 1965, more than 40 percent of adults reported smoking, compared to around 17 percent in 2014. During that same period, tobacco production has dropped precipitously as well.

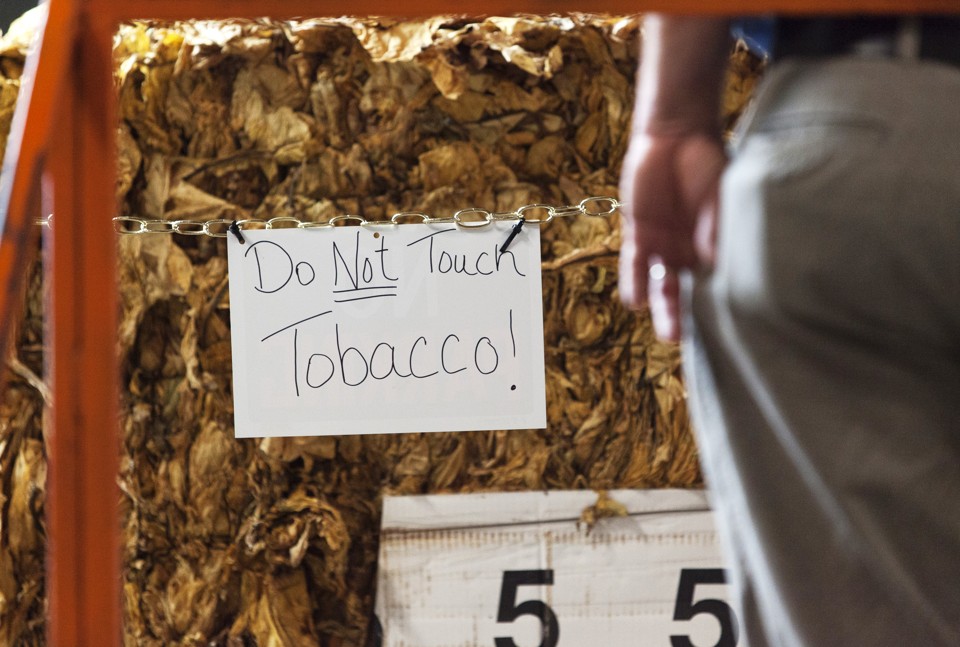

Still, in 2012, the U.S. produced some 800 million pounds of tobacco, and Kentucky—the state with the second-largest tobacco harvest in the U.S. (North Carolina’s comes in first)—is responsible for almost a quarter of that output. Yet even in Kentucky, tobacco farming has waned, forcing many farmers to look into other crops.

Jane Harrod runs a small farm in Kentucky. Her family used to grow tobacco, but she’s since switched over to growing hemp, a somewhat controversial plant—what with the federal ban on marijuana and medical marijuana still being illegal in Kentucky—that the state is currently testing out with pilot programs. For The Atlantic’s ongoing series of interviews with American workers, I talked to Harrod about her family farm, the recession, and why she decided to shift production to hemp. The interview that follows has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Bourree Lam: How did you get into farming?

Jane Harrod: I do landscaping, where I grow native plants. I also farm vegetables and industrial hemp. I'm just a green-thumb person. I grew up on a farm, so being outside, working in the soil, and growing things has always felt like what I should be doing.

My mother was the farmer on our farm. Her father only had daughters, and my mom loved the farm so she went to agriculture school at the University of Kentucky. She didn't do all the physical work, but she ran the farm beautifully with contour plowing, always used cover crops, and protected her topsoil. She didn't get into the herbicides when everybody was going in that direction.

When I was a kid, we had 20 acres of tobacco, 40 to 60 heads of cattle, a milk cow, hogs, and chickens. We also had two teams of mules to mow certain areas of the farm that were too steep to get a tractor on. It was probably the last working small farm in Fayette County, Kentucky, because most of those farms had gone strictly conventional row-crop or were horse farms.

Lam: Did you go to agriculture school as well?

Harrod: I did not. When we were kids, mom dragged us around the fields with her. We grew up knowing this stuff, doing farm chores, and hearing the talk around the table about the crop, how they looked, and what diseases were happening.

We went with mom to the tobacco warehouse when we would sell the crop. Generally, we'd be stripping tobacco in late October if it was an early crop, but more often around Thanksgiving. There was a lot of time spent out in the barn in the stripping room, looking to see if the tobacco was in was in case [meaning the tobacco has picked up moisture from the atmosphere, and can be stripped off the stalk without shattering], and to get it down out of the barn. We learned how to cut tobacco, load it on the wagons, take it to the barns, and climb up in the rails and hang it.

To me, the only good thing about tobacco was that it was such a cohesive community crop. Everybody needed a lot of hands, so we would go back and forth to other farms to help with their crop. Then, they'd help with our crop. In the spring, you'd burn your beds. That was back before the methobromide fumigant was used.

There was so much to do raising a crop of tobacco, but it was the only crop that would give you the return that would pretty much consistently give you a profitable year, and give us enough money to live on. My dad worked a job. Hardly any farmers just farmed, unless they had huge amounts of land. We had a little over 400 acres.

Lam: What’s a typical day like for you?

Harrod: I basically get up, go down to the greenhouse, and water plants. I have a greenhouse where I live in Anderson County, and then I have a greenhouse at my farm in Fayette County, where the hemp is growing.

My brothers live at the family farm, so we help each other out with feeding hogs or watering plants. Then I help with other things around the farm such as moving and rolling bales, picking up tractor parts, going out and buying cattle, or showing up for veterinarian visits. My brother and I work well as a team on the farm, but for me, this is a busy time of year on landscaping. We're into the fall season now. I'll be mostly trying to work on landscape stuff and to put together a reserve of money before we head into the winter. I really like doing the work myself. I love everything about it, and it's kept me pretty darned healthy.

Lam: Is your husband also a farmer?

Harrod: No, we're musicians [just for fun]. We met actually at a hog roast playing music. We appreciated each other's music, and then it turned into love, then marriage, and children. Now we're divorced, but we're still good friends. We had a little farm in Owen County, away from my family farm. He was getting his master's in teaching, and we raised a small tobacco crop. We only had a base of two acres—a very small crop, but that gave us an extra $5,000 or $6,000.

We could probably be called hippies at the time. We weren't big spenders; we grew our own food and raised our two daughters there in Owen County. There were a lot of young people that had moved into the area, because the farmland was cheap. We had an intentional-community situation where we had like-minded people set up a feed co-op and do tobacco together with other crops.

Lam: In 2004, Congress passed the Fair and Equitable Tobacco Reform Act which ended tobacco quotas and a payment program to help producers transition. Tell me about the “tobacco buy-out” and how you got into growing hemp instead.

Harrod: People were like, "Why are we subsidizing this plant that causes cancer and heart problems and all of these health problems?" That all got resolved. What the government (and the USDA) did was say, "We will do a 10-year buyout. We will determine what your last three or four years of growing were, how many acres you had, and then we will pay a certain amount of money to you over 10 years to give you some income back with which you should be trying to transition into other crops."

Hemp has only come in at the very tail end of that. We lost a lot of ponds by eminent domain to build the Interstate 75. The ramps and side roads are right in the middle of the farm. That took away almost 90 percent of our tillable ground. Our farm has struggled since then, because there was not enough ground left to really have a large enough base for a crop to be profitable. This year I’m trying to grow hemp, especially the cannabidiol oil (CBD) from the hemp plant. CBD has to be below 0.3 percent THC to qualify. If you're above that and your crop is destroyed [by the authorities], tough luck. Everybody's very careful about the seed they're growing. We have to go through a very rigorous criminal-background check and paperwork describing our farm and equipment to see if we're actually real farmers.

Lam: Why did you stop growing tobacco?

Harrod: Basically, my brother wanted to keep raising tobacco. I said, "No, we're not going to do that because mom died of lung cancer from smoking cigarettes all her life." I never really liked tobacco because of that. I said, "No. We just have to find another way." Then I did some vegetables for the farmers’ market and CSA [community-supported agriculture], and raised some wholesale produce for some restaurants. We have beef cattle, but the margins are tight.

Lam: Was it a hard decision for you, economically, to stop growing tobacco?

Harrod: Yes, but the returns are not as high as they used to be. Before, there was a support price [the government’s tobacco support program, which ended in 2004, set a minimum price for it] and you knew exactly the lowest amount of money you could possibly get for your crop. People were able to budget on that premise. Now, that price is lower and lower every year because so many other places—South America, Central America, Mexico—are able to do it cheaper.

That made it a lot easier to say, "No, brother, we're not going to dedicate what little bit of good tillable land we have left on this farm to this crop." I've always been in favor of industrial hemp and medical marijuana, but our only option is industrial hemp. When I started to learn about the CBD oil and the great medicinal properties that it had, I thought, "Wow. This is wonderful."

For landscaping, though, during the economic downturn the people that employ me for landscaping are lawyers and doctors and people with high-end lives. But when their dividends were reduced, the landscaper is the first person to go. It was all just this sort of little domino effect, and I lost my home. I still had my farm, and the reason I didn't try to take bankruptcy was because then they would have gone after the family farm. I couldn't do that, so I just kind of threw up my hands.

I really did not feel like I was treated fairly as a human being by the bank. They had bought my loan. I got behind, and they sink you as fast as they can. I had put $40,000 down on that house. I had put on a new roof. They just snatched it fast, and I was looking for ways through some of the governmental programs to see if there was some way we could slow the process down and get caught up, but it just wasn't to be. That was unfortunate, but I just think, my daughters were healthy, I was healthy. The real important things were okay. I just really had to look at it that way to be able to go on and put one foot in front of the other. Then the hemp came along three years ago, and I have great hopes that this will truly be, not a big money-making thing, not get-rich kind of money, but solid.

Lam: How has the decrease in profitability in growing tobacco changed Kentucky’s economy?

Harrod: Once the subsidies for tobacco disappeared and it wasn't as profitable to grow anymore, there's been a lot of people selling their farms. That might be as much due to population growth in our area, but a lot of times it ends up being the farms with the bigger purses that pick up small farms that had relied on tobacco.

A lot of smaller farms have shifted away from small farmers and toward larger conglomerate farms. In our area, that’s happened with horse farms because that's the higher-end commodity. People that are into thoroughbred horses are not necessarily in that to make money. They're in that because it's a great tax write-off, and they already have money. We have one of the largest concentrations of the very best stallions in the world. People say, "Well, [horse farming] creates a lot of jobs." Yes, it does, but most of them are very low-paying jobs. I've worked on those farms, and it’s only the people at the top who make good money. The rest of the folks make barely a living wage.

Lam: How does your work relate to your identity?

Harrod: My identity as a Mother Earth person is very important to me. I think about how healthy America has gotten, and I think we’re at a good turning point in terms of respecting farmers more in this country. I have people who want to hear my stories of my little farm, and there’s a really good push to share information—which is great.

Nobody is getting rich farming; that’s important to know. This country can do better—we have some subsidies, but they go to crops like corn. I really think there needs to be a hard look at the way commodities are bought and sold, and the futures market. The futures market don’t help anybody but the wealthy. It’d be nice to look into that.

No comments:

Post a Comment